THE SPIRITUAL TRAVELER

Looking back at a transformative moment in Auckland that changed the way I travel

New Zealand always delivers. I was in Auckland in April, months before the new Māori Queen, Ngā Wai Hono i te Pō, gave her first, inspiring speech as Queen, I was standing on Maungawhau — Mount Eden — with Dane Tumahai, a local cultural edutainer whose storytelling is part history, part performance, all charm. We weren’t climbing the volcano that day. We weren’t “doing” Mount Eden for the ‘gram. We were doing a pounamu (greenstone) blessing ceremony instead.

I held the stone in my hands while Dane recited karakia. I didn’t know what to expect — maybe a little ritual, a photo, move on. But it wasn’t like that at all. It was quiet. Intimate. Weighty in a way that makes your chest tighten. The stone — cool, smooth, ancient — felt alive. It was connection, lineage, care. Mana. It reminded me that the land, the ancestors, the people — they aren’t distant. They’re right here, and if you stop rushing, they will talk to you.

From the crater rim, Auckland stretched out below — harbors, beaches, islands, the chaotic city unfolding in neat little grids — but my eyes kept drifting back to the maunga (the Māori word for mountain) itself. Terraces, storage pits, remnants of fortified pā — a Māori village You could feel centuries of life etched into the slopes: struggle, survival, celebration, loss, love. Every mound was a teacher. Every crater a quiet testament to stewardship. You can look, or you can see. I saw.

And then came that marvelous thread of history…

Walking with Dane, I thought about the layers beneath my feet. Tāmaki Makaurau — Auckland — means “a city desired by many.” The Māori first settled here centuries ago, drawn by fertile volcanic soils, abundant fisheries, and natural harbors. They built pā on volcanic cones like Maungawhau, creating strong, vibrant communities as Dane tells me. These volcanoes were more than topographical features; they were living landscapes, woven into daily life, spirituality, and strategy. Understanding this history — how people adapted, thrived, and honored the land — made my presence there feel less like cliched tourism and more like witnessing a story still unfolding.

Later, I wandered into the Auckland Art Gallery to see Ngā Taonga Tūturu: Treasured Māori Portraits, and I had the rare privilege of walking it with Nathan Pōhio, the curator. He didn’t just show me objects; he unraveled their stories. Standing in front of a Lindauer painting of Te Hira Te Kawau, a Maori chief from the late nineteenth/early twentieth centuries, Nathan pointed out the posture, the gaze, the subtle details that radiate mana. I could feel the presence of ancestors, the pulse of whakapapa (a central concept in Māori culture referring to genealogy, lineage, and descent, connecting people to their ancestors, land, and the wider universe), and the centuries of memory captured in a single painted face.

We moved slowly from painting to carving to finely woven cloaks. Nathan explained how each object carries mauri, a life force, and how even the tiniest carving or the smallest detail in a cloak encodes knowledge, identity, and history. A tiny hei tiki made me pause; its carved features were exquisite and precise, but the presence it held was immense. Photography and oil painting, adopted in the 19th century, often stood in for carvings in whare tūpuna (ancestral meeting houses), bridging tradition and adaptation. Walking through the exhibition, the gallery itself felt like a living whare tūpuna, humming with the mana of the people portrayed.

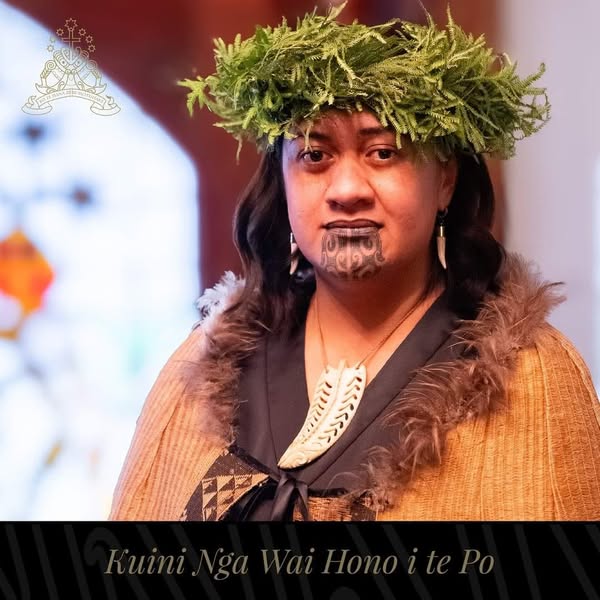

Months later, Queen Ngā Wai Hono i te Pō gave her first public speech. She spoke of Māori identity, language, and heritage — not as relics, but as living, breathing things. She said being Māori is forever. And I thought back to Maungawhau, to the greenstone, to the treasures in the gallery. That April experience felt like a mirror of everything she said — wisdom carried in the land, in ritual, in choices made to honor what came before.

Auckland is just the beginning. Marae in Rotorua welcome visitors with pōwhiri — a traditional greeting ceremony that includes song and earth-cooked hangi. On the South Island, iwi show how ancestral knowledge and environmental care intertwine. And if you want to feel the emotional and mystical heartbeat of this land, Keri Hulme’s The Bone People (1983) is unmatched: a semi-autobiographical, savagely realist novel set on the West Coast of the South Island that won the Booker Prize in 1985. Māori culture isn’t something you passively observe. It asks you to pay attention, participate, reflect, and — if you’re lucky — carry it home with you.

And in fact now as I watch the Queen’s speech and reflect on my time there, what stays with me isn’t the city view. Not the volcanoes, not the harbors. It’s that quiet, profound feeling of connection. The sense that the wisdom of a place, and the people who honor it, can slip into you if you let it.

Travel can be more than movement. It can be listening. A mirror. Something that reshapes how you move through the world, quietly, forever.