WHERE WRITERS WROTE

These literary destinations are worth a visit for the hotels alone

When I grew up in England in the sixties, every schoolchild learned about William Shakespeare’s will bequeathing his second best bed to his wife Anne Hathaway. Even though we were too young to understand the concept of mistresses, or even sex, we knew that something wasn’t quite right. On a school trip tour of his house we saw the immortal bed, which only deepened the wonder of where and to who the first bed went, especially as it was (by our 20th century standards) an ordinary looking bed.

Turns out that the second best bed was commonly considered to mean the marriage bed in Elizabethan times, and therefore the bequest was not a snub but an affectionate affirmation. The first best bed was traditionally reserved for visitors. And beds in general then were status symbols. This was of course before water beds, the ultimate status symbol of all time.

Even the most casual readers have something of an innate fascination for where writers come from, partly because it’s the last place they ever write about. The whole rest of the world, and worlds that don’t even exist, they unfurl as immaculately precise, evocative, vivid tapestries, but they won’t tell you about where they themselves laid their heads. Ray Bradbury did not live on Mars. (He lived most of his life, and died, in Los Angeles.)

There isn’t, ironically, much to see or do in Stratford-upon-Avon, other than visit Shakespeare’s house or see his plays performed by the Royal Shakespeare Company at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre or the retro Swan Theatre, named after one of the 16th century playhouses in London that his plays were originally staged in.

Here, however, are some fun places to visit, where writers wrote and there are great places to stay. Where, you know, you can think about literature, in a relaxed, unhurried way.

LONDON

Hotel: The Bloomsbury

Literary cred: Virginia Wolff and the Bloomsbury Group

The Bloomsbury is a landmark building designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens back in the mid-1800s, and renovated in 2017 by a team led by designer Martin Brudnizki, (who more recently designed the Hotel Fouquet’s in New York City).

The hotel has serious neighborhood literary heritage, referencing boldly as it does the famous Bloomsbury Group of writers, philosophers and stray intellectuals who used to convene at, mostly, Virginia’s Woolf’s house in this central London area, part of the borough of Camden. The hotel’s wood-paneled library has numerous first edition books dating from the 1930s, including ones by Woolf, John Maynard Keynes, and E.M. Forster. And there’s a restaurant named after Virginia Woolf’s famous character, Mrs. Dalloway, the Dalloway Terrace, which, the hotel will tell you, resembles a secret garden and is very popular for afternoon tea.

The Bloomsbury Club Bar is straight out of the Jazz Age, with a tongue-in-cheek menu that features an intricate and comprehensive diagram of the group’s lustful exploits. Dorothy Parker, who had her own famous and infamous gathering at the Hotel Algonquin in New York, known as the Round Table, said of the Bloomsburys that they “lived in squares, painted in circles and loved in triangles”.

On Saturday mornings the hotel offers guests a complimentary historic walking tour of the neighborhood and 20 of its typical London leafy squares, which is about 15 more than you need to see to, er, get the idea.

NEW ORLEANS

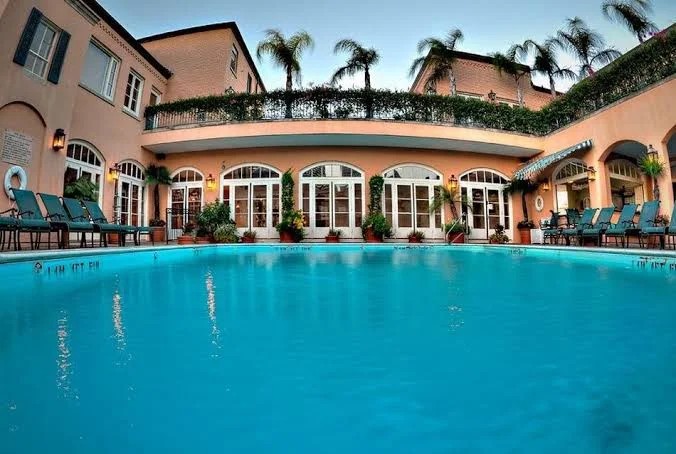

Hotel: Hotel Monteleone

Literary cred: Tennessee Williams, Lillian Hellman, Truman Capote, Anne Rice

Williams and Capote were two of the 20th Century’s greatest writers, and, given they were both openly gay, scandalous for their time. A Streetcar Named Desire and In Cold Blood, to name just one each of their plays and novels, are columns in the Pantheon of American literature. Capote was born in New Orleans (as were Lillian Hellman and Anne Rice) and Williams was born in Mississippi but moved to New Orleans and settled there as an adult. Hellman was primarily a playwright, most famous for Little Foxes, and Rice wrote Interview With a Vampire and the Vampire Chronicles sequels.

New Orleans, maybe uniquely among American cities, retains an eternal gothic sensibility, as if at one arbitrary and hard to discern moment it was frozen in place, and always will be. The Monteleone is the standout hotel in the French Quarter and has been around since 1886 and looks and feels like a classic European top hotel that’s been around for a century or two.

And the Monteleone is not unaware of the writerly pull of the French Quarter, duly characterizing some of their best rooms as literary suites, inspired by the giants of letters who stayed there — long after, to clarify, they toiled in humbler accommodations nearby at the beginning of their careers. There’s the Faulkner Suite, named after William who wrote his first book, The Marble Faun, a compilation of poems no one remembers, and his first novel, Soldier’s Pay, in an apartment in the French Quarter. Capote claimed whimsically that he was born at the hotel (he wasn’t) but clearly loved it and, rightfully, has a suite in his honor. Hemingway gets the penthouse, where Union troops once stayed after the Civil War.

The hotel is ornate and the architectural style is the one known as Beaux Arts. Outside its doors and bright sandstone colored walls, the city looks squalid, although it’s not really. The bar and restaurant are, and have long been, destinations. The Criollo restaurant bills itself as “Coastal Italian meets refined southern dining”, which just sounds confusing and probably a bit overwrought. But it’s great.

BRAEMAR, SCOTLAND

Hotel: The Fife Arms

Literary cred: Diana Gabaldon

Diana Gabaldon started out as a science writer and editor, and academic, before writing her first Outlander book — she’s up to nine now — the hugely beloved sci-fi/historical romance series that, of course, is a hugely beloved TV series. She’s American, lives and has lived most of her life in Arizona and as far as anyone knows has never been to The Fife Arms. Which, if true, is her loss, (As it is mine! I was invited last year and couldn’t go! I will not throw stones at Madame Gabaldon).

But the awesome Scottish Highlands feature so prominently in her novels that they are, in effect, a character. Scotland is a rugged country. The Romans conquered the whole known world, got here and couldn’t beat the Scots and literally went home. It’s rugged topographically and in spirit (and spirits), and is composed of some of the most dramatic landscapes and coasts and cities and high northern hemisphere, Viking-lore-soaked islands in the world. Scotland is not known for its food, let’s be clear, although I for one love a good haggis. And possibly a bad one. I’m not entirely sure of the difference.

The Fife Arms is one of the great hotels of the world, not least for its gorgeous setting in the center (more or less) of the Cairngorms National Park. The original building was a Victorian-era coach Inn, and it was mightily and gloriously renovated and designed to be a top luxury destination by husband and wife team Iwan and Manuela Wirth, who opened it in Fall of 2018. It looks a touch Hogwarts, from a distance.

The hotel has 46 rooms and suites, all of which are exquisitely rendered. To say they have old world charm is cliched, but true, but more accurately these are rooms you want to live in for a while. Another way of putting it is these are rooms that could potentially bankrupt you, not because they are outrageously expensive, but because you might never want to leave, and, you know, there comes a point…

There are two bars, including a fabulous one with a flying stag hanging from the ceiling. And there are two restaurants, in which, I have on very reliable sources, the food is untypically excellent.

NORTH HATLEY, QUEBEC

Hotel: Manoir Hovey

Literary Cred: Louise Penny

Now here’s a hotel you couldn’t get the writer to leave, apparently.

I mean, not that they wanted her to. But she stayed there so much she invented the fictional village of Three Pines based on the hotel’s quite magical setting on a lake in the Eastern Townships of Quebec, and based the hotel Manoir Bellechasse that’s central to A Rule Against Murder, the fourth book in the Chief Inspector Gamache series, on Manoir Hovey.

The hotel — the real one, the one you can go to — is a 30 acre complex of main building, cottages and cabins, and a lakeside Pavilion with several airy, bright rooms and suites. There are two restaurants and both are Michelin recommended, which is the Michelin version of a massive tease. The Hatley restaurant is the fine dining domain of a master chef, Alexandre Vachon, who is native to the area and cooks immaculate food. There’s plenty of sumptuous seafood dishes and a special vegetarian menu for those who want it and for the property to show off its home grown ingredients. Le Tap Room Bistro, a quixotically half French, half English named bar with great food is under a century old roof and also under the purview of Vachon.

Honestly, this is a place you could stay, lose track of time, leave after a week and think you’d been there for three months you’d be so relaxed and pampered. And what’s wrong with that? But if you go there, you should wander the area, not just because it’s all been translated fictionally into Three Pines (and the TV show with Alfred Molina was filmed around there, although more specifically in the nearby village of Saint-Armand). Visit the Abbey de Saint-Benoit-du-Lac, a Benedictine monastery famous locally for their evening chanted benedictions, and their cheeses and ciders. Monks, at least there, know how to live.

OXFORD, MISSISSIPPI

Hotel: The Oliver Hotel

Literary Cred: William Faulkner

Oxford, named after the city in England, in the hope of inspiring a similarly world-renowned university, is more permanently linked with arguably America’s greatest writer, William Faulkner. Born in Albany, MS, his family moved to Oxford when he was about four years old, and he spent most of his life there until dying in 1962, except for brief periods in Virginia, where he taught for a year, and Hollywood, where he wrote movie scripts for producer Howard Hawks for a few months, before asking Hawks if he could work from home. Hawks, naturally, thought Faulkner meant his home in Los Angeles. Faulkner didn’t, he meant Oxford, and returned there, mailing future script pages to the studio.

Oxford is a special town. I lived there for a year fifteen years ago and I still miss it and my many friends. It’s slow and sleepy, in a wonderful way. It’s pretty much unbent by modern architecture and ambition, and although it’s no longer the little known Southern enclave, preserved in antebellum amber, that it was, it’s still unhurried, still friendly. And there’s great food — Southern star chef and restaurateur John Currence has several of his original restaurants here.

Most of the life and culture of Oxford revolves around The Square, on one corner and at the center of which is America’s best bookstore, Square Books (with a couple of annexes, Off Square Books and Square Books, Jr., dotted around the square like pieces on a Monopoly board). The best restaurants and bars are there, Currence’s City Grocery being the crown jewel, although his Snackbar a few blocks away is damn close.

There’s a new generation of brilliant writers living in Oxford today, all in walking distance of Faulkner’s Rowan Oak home. (It’s also a short walk between Faulkner’s house and grave in St Peter’s Cemetery, although it took him 60 years to get there). Novelists Tom Franklin and Lee Durkee, poet Beth Ann Fennelly, crime writer Ace Atkins, legendary journalist and author Curtis Wilkie, America’s best food writer John T. Edge, ESPN’s Wright Thompson and humorist Jack Pendarvis are some of the greatest wordsmiths in the English language, and they’re all neighbors. So is Faulkner family member Larry Wells — he was married to William’s niece Dean — who is a writer and publisher and has often graced WONDERLUST.

The Oliver Hotel is a relative newcomer to Oxford (by which I mean, “any new institution”, and it’s not even a new building but a refurbished, hitherto nondescript hotel). It opened in 2015 as a boutique-style alternative to the town’s purely functional hospitality options. It’s elegant and the rooms are good. It’s like a family’s smart kid who went away and saw the world and came back and looks different from everyone else.

It costs twice as much as other hotels in the area, of which there are a lot because this is a college town, but it’s the best, most comfortable. The Nightbird is a speakeasy-type bar, which always seems to be the default way of describing a bar a few notches above a saloon but otherwise nothing spectacular.

I don’t mean this pejoratively, but don’t eat there! Because there are too many spectacular restaurants on and off the Square to visit, including the ultimate comfort-foodest of comfort food eateries, Ajax.

JAMAICA

Hotel: Golden Eye

Literary cred: Fleming, Ian Fleming

The writer of the James Bond books, Ian Fleming, discovered Jamaica in July, 1943, during the Second World War, when he was in British Naval Intelligence. He said it rained for four days straight but he loved it and pledged that if he survived the war he’d return and build a home there. He did, and he did, choosing a plot of land on the North shore, on the corner of a then banana-exporting port called Oracabessa, which means “Golden Head.” He later called his home, from where he wrote all his Bond books, Golden Eye.

(But he didn’t write GoldenEye — that’s a novelization by John Gardener of the Bond movie produced 30 years ago, thirty years after Fleming died in 1964.)

Fleming treasured Golden Eye and often wrote about how he lamented not spending more time there, due to traveling to just about every other corner of the world, often as a journalist, often just because he could.

Fleming treasured Golden Eye and often wrote about how he lamented not spending more time there, due to traveling to just about every other corner of the world, often as a journalist, often just because he could.

Island Records founder Chris Blackwell bought Golden Eye in 1977 and in 2010 turned the property into a hodge podge of a hotel, which has become an assortment of marvelous beach villas and huts, and cottages on the lagoon. Fleming’s original five bedroom house is rentable as a stand alone, very private villa.

They don’t really have a restaurant per se, but don’t need one, with two cool bars serving principally Jamaican food (plus the obligatory concession to food Westerners recognize) — Bizot Bar, around a pool on Low Cay Beach, and Bamboo Bar on the sand of Button Beach, about as low key and relaxed and idyllic as it gets.

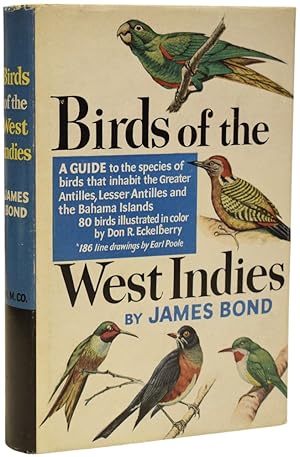

I once visited Chris and stayed a night at Golden Eye, when it was still his home, in the late 1990s. Fleming’s desk is still where it was when he was alive, and on top of a small stack of books was a guidebook, Birds of the West Indies, by James Bond. Fleming took the name of his immortal spy from the author of this book, looking, he said, for as bland and unremarkable a name as he could possibly find for 007.

PARIS

Hotel: Hotel de Crillon

Literary Cred: The Père Lachaise Cemetery

Technically, no one wrote anything here, unless you count the gravestones. Père Lachaise, named after Père François de la Chaise, priest and confessor for Louis XIV, is the largest cemetery in Paris and supposedly the most visited in the world, although how anyone knows that is beyond me. It is the final resting place — the last chapter — for a dizzyingly eclectic array of great writers.

With 70,000 plus graves, they’re not exactly rubbing shoulders with each other, but Oscar Wilde, Honoré de Balzac, Colette, Molière, Richard Wright, Marcel Proust, Guillaume Apollinaire, Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas are all buried here. (And Edith Piaf and Jim Morrison too – Morrison’s grave is apparently the most trafficked of all.)

It’s a top tier tourist site in Paris, complete with guided tours, including a spurious-sounding “haunted” one. That’s a stretch, although it does promise some fun secrets, and that’s not a stretch.

Paris is not short of excellent hotels. The George Cinq, the Ritz, the Hôtel Plaza Athénée, the Saint James Park and Le Bristol are all classics and solid choices, and that’s just the old, big ones. There are dozens of magnificent boutique hotels, especially in Le Marais.

But my favorite is Hotel de Crillon, on the Place de la Concord, which I always found to be that particularly French combination of understated quirkiness and overstated elegance. Its location compresses the heart of Paris into a tourism theme park: a stroll from the Champs-Elysees and the Arch de Triomphe and, in the other direction, the Jardin des Tuileries and the Louvre.

The hotel’s main restaurant, L’Ecrin, is one of the best restaurants in Paris and I say that from deep experience and fond memory.

Its ordinary rooms are beautiful and its suites are spectacular — some have small terraces and all have the traditional tall, heavy windows, thickly curtained. Everything is luxurious, but not in a strained way, because the hotel is comfortable in its own skin. It was born luxurious. Originally a palace commissioned by Louis XV as a government building in 1758 (where France signed a treaty with the fledgling United States in 1778, becoming the first country to officially recognize us), it became a hotel in 1909, owned by the Louvre.

And, sort of coming full circle, Ernest Hemingway set a key scene of The Sun Also Rises in the hotel lobby, and again references it in “The Snows of Kilimanjaro”. He loved the place.